Introduction: Where Trees Whisper, Life Thrives.

How Trees Communicate: Imagine walking through a dense forest just after a gentle rain. The air is thick with the scent of wet leaves and earth. Sunlight flickers through the tall canopy, casting dancing shadows on the mossy floor.

You pause to listen — not just with your ears, but with your whole being. The forest is alive, but not in the way most of us think. Beneath the surface and beyond our senses, something extraordinary is happening: the trees are talking.

This isn’t a tale of fantasy, but one grounded in modern science and ancient wisdom. Forests are not mere collections of trees. They are vast, intricate societies — living, breathing, and communicating. For centuries, indigenous communities believed trees could feel, respond, and even remember.

This article is a journey into that hidden world, where trees whisper warnings and nourish their kin and even “walk” in search of light. Along the way, we will uncover the science behind their communication, their role as timekeepers and climate guardians, the existential threats they face, and why saving them is crucial for our survival.

The forest is calling. Let’s step inside.

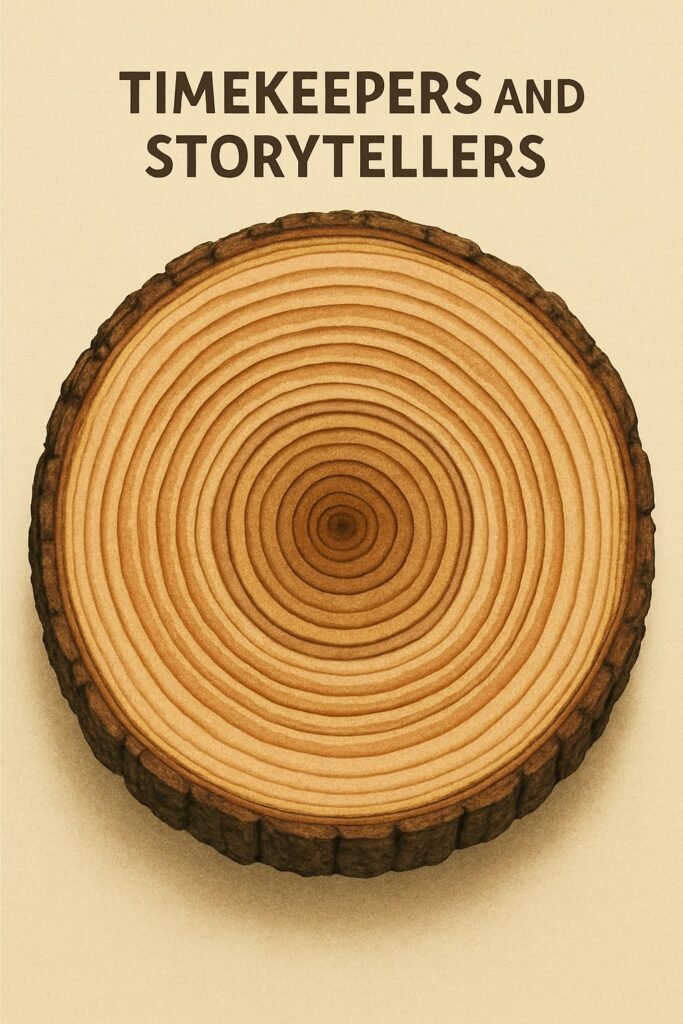

The Memory of Trees: Nature’s Timekeepers and Storytellers

While we marvel at trees for their grandeur and wisdom, scientists have discovered that they are also natural historians, silently recording the stories of climate, disaster, and life in their very rings. This field of study — known as dendrochronology — allows researchers to analyze tree rings to understand past weather, droughts, floods, volcanic eruptions, and even human activity.

Each year, a tree adds a new layer to its trunk — a ring. Thicker rings indicate favorable growth conditions such as adequate rainfall and moderate temperatures. Narrow rings suggest drought or harsh winters. By comparing ring patterns across trees from different regions, scientists can reconstruct climate events from hundreds, even thousands of years ago.

Some studies conducted on this topic –

- A 2013 study, “Continental-scale temperature variability during the past two millennia”, published in Nature Geoscience, showed that tree rings helped reconstruct global temperature trends going back more than 2,000 years, revealing patterns of natural climate variability before industrial times.

Tree rings were a crucial proxy in this study due to their annual resolution and sensitivity to temperature and precipitation. By analyzing the width and density of tree rings from various species and locations, researchers could infer past climate conditions with remarkable precision.

- Harold C. Fritts, in his book Tree Rings and Climate (1976), demonstrated how tree rings reflect drought, temperature, and precipitation variability, showing how trees respond collectively to environmental stress. This shared sensitivity to climate conditions laid early groundwork for understanding the interconnected, communicative behavior of trees within forest ecosystems.

- In the Himalayas, scientists have analyzed deodar tree rings to reconstruct monsoon patterns spanning the last 1,000 years. These rings capture annual changes in rainfall, revealing periods of intense drought or strong monsoons. Such studies help understand long-term climate variability and improve predictions of future monsoon behavior in South Asia. [Ref: “A 694-year tree-ring based rainfall reconstruction from Himachal Pradesh, India”, published in Climate Dynamics in 2009 by R. R. Yadav, J. Singh, and B. Dubey.]

These findings make it clear: trees are not passive observers — they are living libraries. In fact, some indigenous cultures refer to ancient trees as “standing elders” who carry the memory of the land.

By studying trees, we don’t just learn about them, we learn about ourselves, our environment, and the changes we have triggered over centuries.

Nature’s Circle of Care: How Trees and Creatures Help Each Other

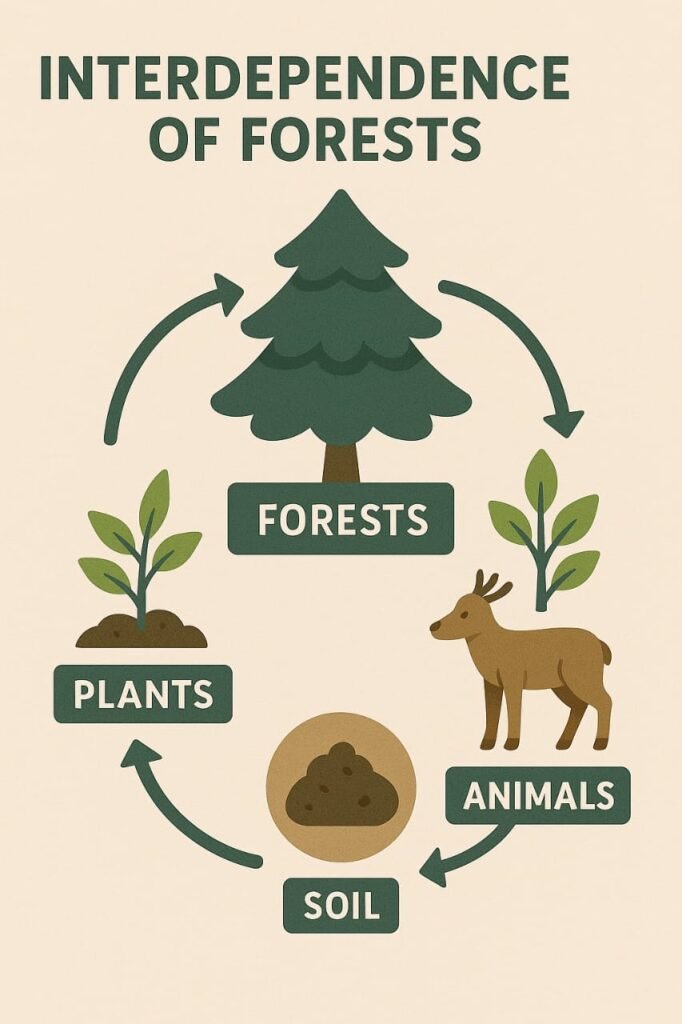

From fungi and bacteria to birds, insects, and mammals — everything in the forest plays a part. Trees give shelter to birds and animals, offer fruit and seeds, and provide shade to ferns, mosses, and small plants. In return, animals such as hornbills, monkeys, and bats help disperse seeds far and wide. Pollinators like bees and butterflies ensure the next generation of trees and plants. This intricate network of relationships is known as mutualism or symbiosis.

The WWF in its Living Forests Report (2011) emphasized that loss of key dispersers can trigger a chain reaction, eventually affecting the entire forest’s biodiversity.

The report explained that when important animals like birds, monkeys, or elephants, who spread seeds, disappear, it causes big problems for the forest. These animals share a symbiotic relationship with trees: trees provide them with fruits and shelter, and in return, the animals help spread tree seeds. Without these animals, fewer new trees grow, weakening the forest. This shows how closely trees and animals depend on each other, and why protecting both is vital for forest health.

[Ref: https://awsassets.panda.org/downloads/living_forests_chapter_1_26_4_11.pdf]

Forests aren’t just biological spaces — they are living systems where cooperation ensures survival.

Do Trees Move? The Walking Palm Mystery

Let’s go into the South American rainforest, where you might hear stories about trees that can walk. It sounds like a myth, but it’s based on a real tree called the Walking Palm (Socratea exorrhiza). This tree has long, stilt-like roots that grow above the ground. Some scientists think it can slowly “move” by growing new roots toward sunlight or better soil and letting old roots die. So, in a way, the tree may shift its position over time.

However, many researchers argue there is no solid evidence that the tree changes location. Still, its unique roots show how trees adapt and survive. However, this claim has been largely challenged by scientific scrutiny.

A 2005 study by tropical ecologist Gerardo Avalos refuted the walking theory, concluding that there was no evidence to support actual locomotion in the tree. While the Walking Palm’s unique root system may help it stabilize in swampy soil or after minor landslides, movement in the literal sense remains more myth than reality.

[Reference: Avalos, G. (2005). Does the Walking Palm Walk? Biotropica, 37(1), 44–46.]

The report “Socratea exorrhiza: The Walking Palm” by Cecilia G. Williamson and Helene C. Muller-Landau. Published in 2024 as part of The First 100 Years of Research on Barro Colorado: Plant and Ecosystem Science, Volume 2, explains the unique features of this rainforest tree. The report shares detailed research on how the tree grows, survives, and fits into the forest’s ecosystem. It helps us understand how special and smart nature can be.

This unseen network and subtle movement prove a vital truth: in forests, everything is connected — even when it seems still.

How Trees Communicate: The Forest’s Secret Language – A Network of Sharing, Support, and Survival.

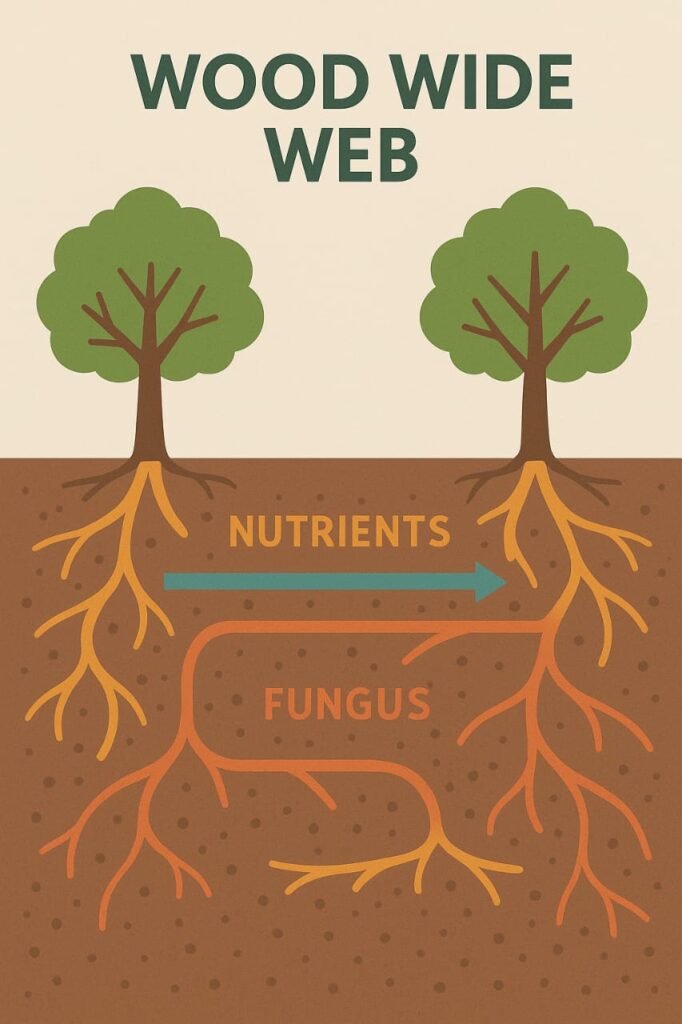

Imagine you’re standing beneath a centuries-old oak tree. It appears still, majestic, and silent. But beneath your feet lies a secret world — a vast underground network of roots and fungi, where trees whisper to one another, share resources, and protect their young. This isn’t fantasy — it’s the scientifically documented “Wood Wide Web.”

Dr. Suzanne Simard, a forest ecologist at the University of British Columbia, made a groundbreaking discovery: trees are interconnected and rely on one another through a vast underground fungal network known as the “Wood Wide Web.”

She said in her book, Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest,

“The trees soon revealed startling secrets. I discovered that they are in a web of interdependence, linked by a system of underground channels, where they perceive and connect and relate with an ancient intricacy and wisdom that can no longer be denied.”

Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest.

(Dr. Suzanne Simard)

In plants, there are symbiotic relationships between fungi and the roots of the plants. These symbiotic relationships are called “Mycorrhizae”. The fungus helps the plant by increasing water and nutrient absorption, especially phosphorus, while the plant provides the fungus with sugars and carbohydrates produced through photosynthesis. Through these mycorrhizal fungi, trees exchange nutrients, send distress signals, and support weaker community members.

Dr. Simard explains how older trees, often called “Mother Trees,” can recognize their kin and supply them with nutrients and water through underground fungal networks. She compares these nurturing behaviors in trees to human parental care, highlighting the social dynamics of forests and their crucial role in evolution.

In her words,

“Forests are not simply collections of trees; they are complex, cooperative networks that resemble human communities in many ways.”

“The older trees can discern which seedlings are their own kin. The old trees nurture the young ones and provide them food and water just as we do with our own children. It is enough to make one pause, take a deep breath, and contemplate the social nature of the forest and how this is critical for evolution. The fungal network appears to wire the trees for fitness. And more. These old trees are mothering their children.”

In her experiment, she injected radioactive carbon isotopes into trees and tracked their movement. What she found was astonishing: the carbon moved from one tree to another, not through the air or falling leaves, but through the soil, via fine, thread-like fungi known as mycorrhizae. This was the first concrete evidence that trees can share nutrients and information underground.

These fungi form symbiotic relationships with trees. They attach to roots and extend far into the soil, increasing the tree’s access to water and minerals. In return, the fungi receive sugars and carbohydrates produced by the tree during photosynthesis. But the relationship goes beyond a simple exchange — it’s a networked system, a living internet of the forest.

Trees under attack by pests release chemical signals through roots and air to warn others. Neighboring trees then activate their defenses in advance.

Key Functions of the Wood Wide Web:

- Communication: Trees warn each other of attacks.

- Resource Sharing: Trees support struggling neighbors, especially seedlings.

- Kin Recognition: Mother trees nurture their offspring more than unrelated saplings.

- Ecosystem Stability: Fungal networks reduce stress during droughts and enrich forest resilience.

“A forest is much more than what you see. It’s a community of minds below ground.”

— Dr. Suzanne Simard, TED Talk, 2016

“Fungal networks are the cardiovascular systems of the forest.”

— Merlin Sheldrake, author of Entangled Life

This hidden network reflects the essence of human communities—sharing, nurturing, and growing together. In a world often focused on competition, forests offer a powerful reminder of the strength found in cooperation.

Guardians in Peril: Why Forests Need Our Help Now

Once upon a time, vast green kingdoms stretched across continents, teeming with life, pulsing with whispers of trees and songs of birds. But today, those mighty forests are vanishing, fragmenting, and gasping for survival. The protectors of life — the very trees that sustain our breath — are under siege.

The Unfolding Crisis

Despite their resilience and ancient wisdom, forests are not invincible. Human activity — particularly deforestation, mining, urban expansion, and climate change — is dismantling these intricate ecosystems faster than they can regenerate.

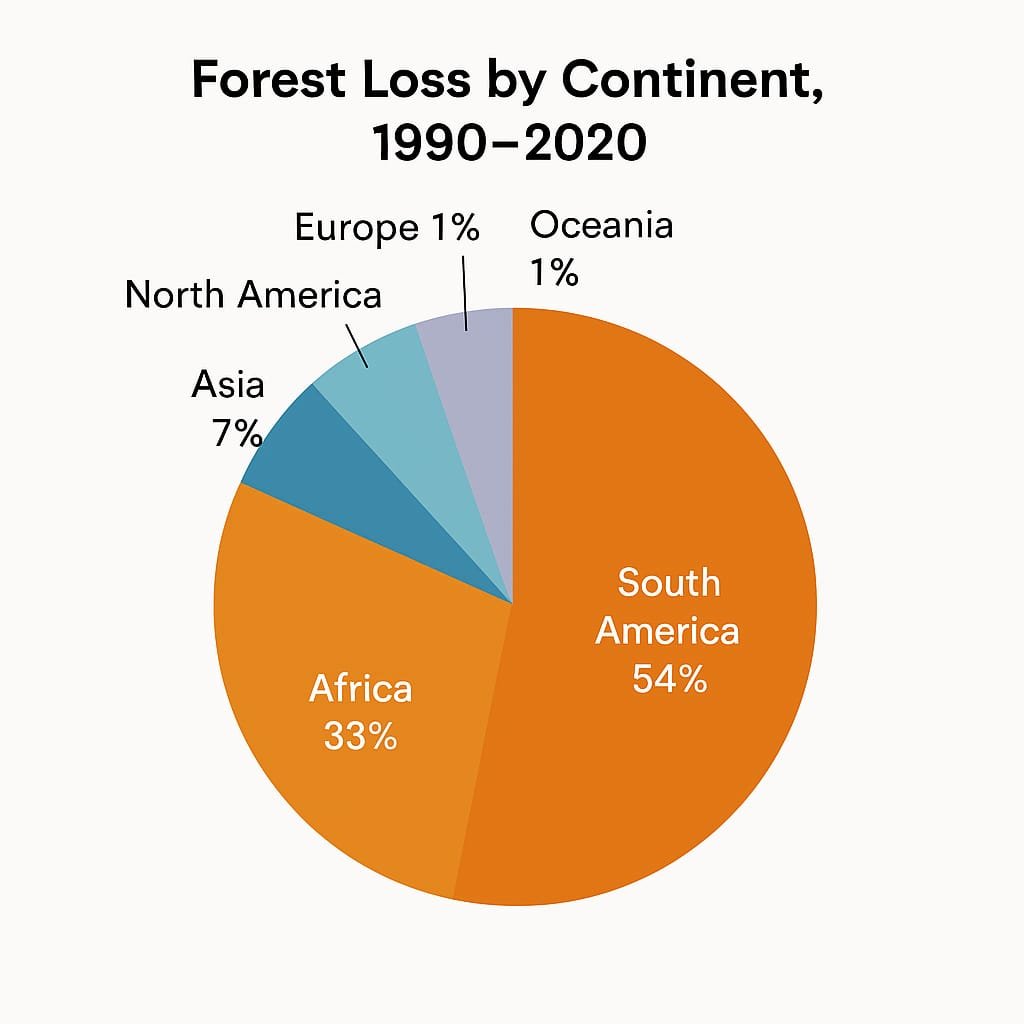

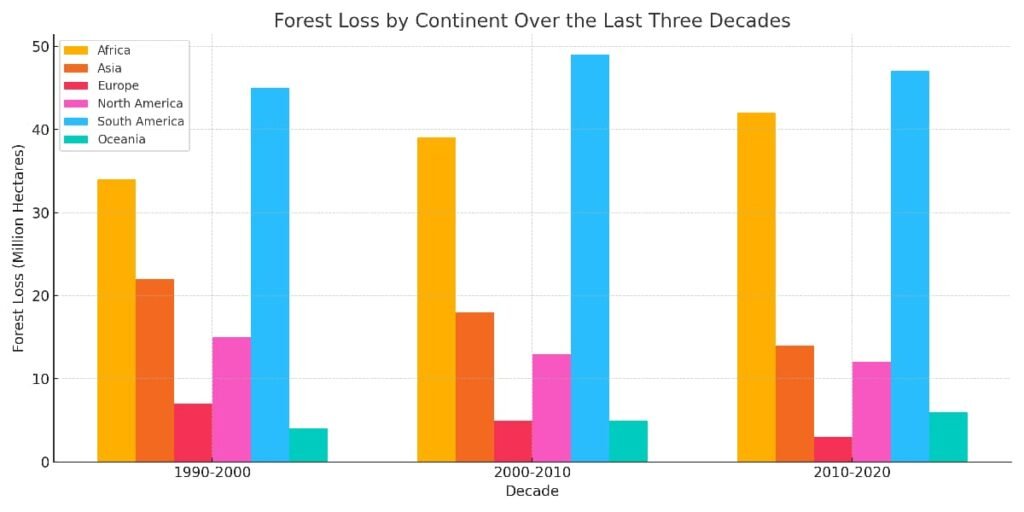

According to the FAO’s Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, the world has lost 420 million hectares of forest since 1990. That is an area larger than India. And the rate continues: between 2015 and 2020, we lost 10 million hectares annually.

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) warns that deforestation in tropical forests alone could lead to the extinction of up to 10,000 species annually. These losses are not just numbers — they are broken homes, silenced songs, and unraveling ecosystems.

“When we destroy forests, we’re not just felling trees — we’re cutting the web of life itself.”

— Inger Andersen, Executive Director, UNEP

As guardians of air, climate, and biodiversity, trees do not need us — we need them. And if we want to keep hearing their underground whispers and bask in their healing shadows, the time to act is now.

Major Challenges to Forest Conservation

As the world races to protect forests, it is not running on a smooth path. The challenges are towering, as complex and intertwined as the roots of an ancient banyan tree. To truly understand the forest crisis, we must walk through the thick underbrush of human greed, political inertia, and environmental injustice.

1. Relentless Deforestation and Land Conversion

Every year, millions of hectares of forest are cleared for agriculture, mining, infrastructure, and urban expansion. According to the FAO Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020, the planet lost nearly 420 million hectares of forest since 1990 — an area larger than the size of India.

Large-scale industrial agriculture, especially for palm oil, soy, and cattle, accounts for 80% of global deforestation, especially in tropical regions like the Amazon, Southeast Asia, and Central Africa.

Reference: FAO (2020). Global Forest Resources Assessment.

2. Illegal Logging and Weak Governance

Illegal logging, often backed by corruption and criminal networks, is a major threat to forest health. It strips forests of high-value species, disrupts ecosystems, and deprives nations of billions in lost revenue.

A report by INTERPOL and the World Bank estimates that illegal logging generates USD 30–100 billion annually in criminal proceeds. Forest-rich countries with weak legal enforcement often suffer the most.

Reference: INTERPOL & World Bank. Justice for Forests: Improving Criminal Justice Efforts to Combat Illegal Logging. (2012)

3. Climate Change: A Double-Edged Sword

Forests regulate climate by absorbing CO₂ — but now, climate change is turning forests from allies to victims. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and extreme weather events are increasing the frequency of forest fires, pest outbreaks, and disease.

For example, Canada’s 2023 wildfire season burned over 18 million hectares, releasing more greenhouse gases than the country’s entire industrial sector that year.

Reference: Natural Resources Canada. 2023 Wildfire Summary Report.

4. Human-Wildlife Conflict and Encroachment

As forests shrink, animals venture into human settlements in search of food and shelter. This results in conflicts, retaliatory killings, and habitat fragmentation. At the same time, forest-dwelling communities are often displaced without fair compensation or consultation.

In India, more than 500 people die annually due to conflicts with elephants and big cats — a consequence of vanishing wildlife corridors and shrinking forest cover.

Reference: Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC), India.

5. Loss of Indigenous Rights and Knowledge

Despite protecting forests for generations, indigenous communities are often sidelined or evicted in the name of development or conservation. This not only violates human rights but also causes the loss of traditional ecological wisdom, which is crucial for sustainable forest management.

Reference: United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII).

Efforts for Forest Conservation

The ancient trees, the whispering canopies, and the hidden mycorrhizal networks may seem timeless, but their fate now lies in human hands. Saving forests is not a distant dream; it’s a pressing necessity. Around the world, scientists, indigenous communities, governments, and everyday people are rising like saplings toward the light, striving to ensure a greener future.

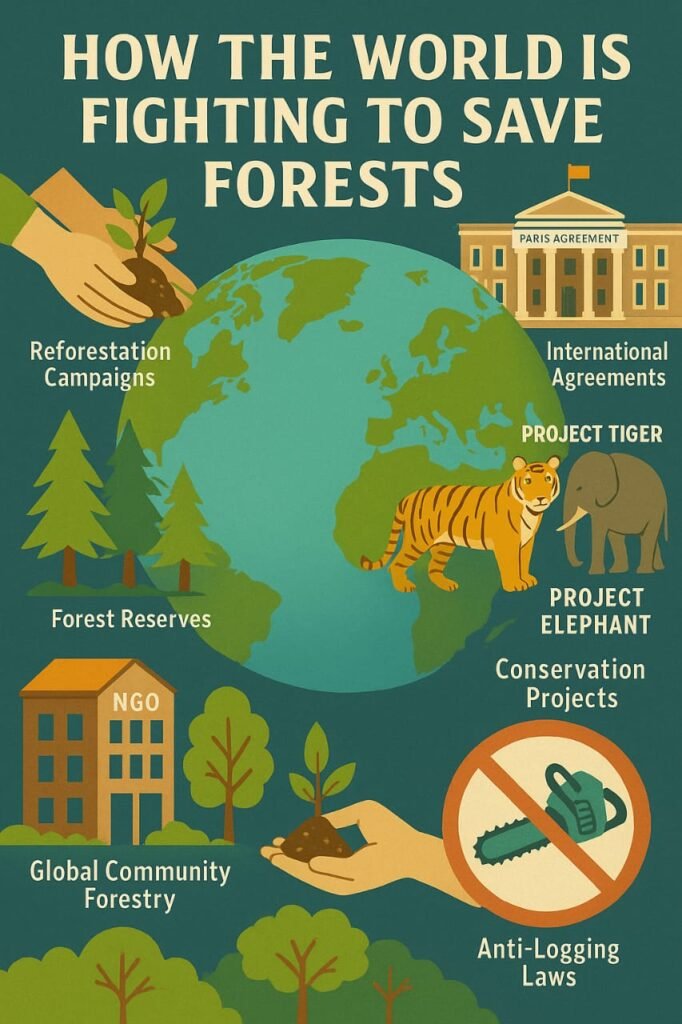

How the World is Fighting to Save Forests

As the sun sets behind the last green canopy of many parts of the world, a quiet alarm is ringing across continents — our forests are vanishing. But unlike the silence of felled trees, a loud and determined global movement is rising to protect what remains and restore what is lost.

International Agreements and Alliances:

1. Global initiatives for Forest Conservation

At the global level, several frameworks are working toward forest protection:

The Bonn Challenge (2011): A global effort to restore 350 million hectares of degraded forest land by 2030.

Global Commitments: In 2021, over 140 countries signed the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use during COP26, pledging to halt deforestation by 2030.

WWF’s Role: The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) pushes for “zero net deforestation” through science-based policies, local engagement, and awareness campaigns.

WWF’s Trillion Trees Initiative aims to restore and protect one trillion trees by 2050 in collaboration with BirdLife International and WCS.

Financial Incentives – REDD+: The UN-backed REDD+ program rewards countries like Costa Rica and Guyana for conserving forests, treating them as carbon sinks and community resources.

Technology & Monitoring: Platforms like Global Forest Watch (by WRI) use satellites and AI to track forest loss in near real-time, enabling faster response to threats.

2. Indigenous and Community Forest Management

A 2018 study published in Nature Sustainability found that forests under indigenous and local community management show lower deforestation rates than state-controlled ones.

In the Amazon, territories managed by indigenous communities have been shown to store more carbon and maintain better biodiversity.

Reference: Schleicher, J. et al. (2018). Nature Sustainability.

3. Reforestation and Afforestation Projects

Countries are initiating large-scale planting efforts:

India’s Green India Mission: Targets 5 million hectares of afforestation and improved ecosystem services.

China’s Great Green Wall: Has planted over 66 billion trees to combat desertification since the 1970s.

Africa’s Great Green Wall aims to restore 100 million hectares of land across the Sahel by 2030.

But experts warn: “Planting trees is not enough. The right tree in the right place with the right care” is crucial. Monocultures can harm biodiversity and water tables.

Reference: UNCCD, MoEFCC (India), FAO.

Today, the global fight to save forests is multifaceted, involving not just governments and NGOs but also local communities, businesses, and individuals.

Some of the prominent methods being adopted include afforestation programs, sustainable logging practices, the promotion of eco-tourism, legal protections through forest acts, the assertion of indigenous rights, technological interventions such as satellite monitoring, and large-scale awareness campaigns.

Many projects run for the conservation of wildlife, such as Project Tiger, Project Lion, Project Elephant, etc, also play an important role in the conservation of forests.

What Can We, the Citizens, Do?

Plant more trees: Contributing to reforestation by planting trees in urban areas and deforested regions can help maintain balance in nature.

Reduce deforestation: Support sustainable practices like using eco-friendly products and avoiding products that contribute to illegal logging or unsustainable farming.

Support tree-friendly policies: Advocate for laws that protect forests and encourage tree planting and preservation.

Recycle paper: Using less paper and recycling it helps reduce the demand for cutting down trees.

Spread awareness: Educate others on the importance of trees in providing oxygen, improving air quality, and preventing soil erosion.

Buy sustainably sourced products: Choose wood products or palm oil certified by organizations that ensure sustainable farming and logging practices.

As environmentalist Jane Goodall says,

“What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make.”

Conclusion:

Forests are not just groups of trees; they are interconnected ecosystems where everything, from the underground fungal networks to pollinators, works together. However, deforestation, climate change, and lost species are putting them at risk.

Saving forests is more than just planting trees; it’s about understanding and restoring these vital systems. The health of forests directly impacts our future. Let’s be the generation that listens to the forest’s call and takes action to protect and preserve it for future generations.

Stay Connected with Junglefizz

We are committed to exploring the mysteries of nature—trees, animals, birds, rivers, and the delicate balance of ecosystems. Stay with us as we bring you more stories, scientific insights, and updates on conservation efforts from around the globe.

Q1: What is the Wood Wide Web?

It’s a network of underground fungi that connects trees, helping them share resources and information.

Q2: Can trees walk?

The Walking Palm appears to “move” by growing new roots in new directions, but it’s a debated topic in science.

Q3: How can I help forests?

Plant trees, reduce wood/paper use, support eco-friendly products, and promote awareness.